The Give and Take of Village Life

We must be learners before we can become teachers.

AFRICACULTURE LEARNING

Daniel Dore

5/28/2024

The Give and Take of Village Life

We lived in two different villages while serving in West Africa from 1990 to 2018. (We also lived in a more developed town, on two different occasions, but that is another story.) Living in a remote village, with no electricity or running water, was a unique experience. Everything started simple—pulling water from our hand-dug well by the rope and bucket method, using candles and kerosene lamps to read by at night, and keeping a cake of ice in a picnic cooler for a refrigerator of sorts. Eventually we upgraded to a generator and well pump, a few solar panels to run lights, and a kerosene refrigerator. Our relationships with our village neighbors also developed over time.

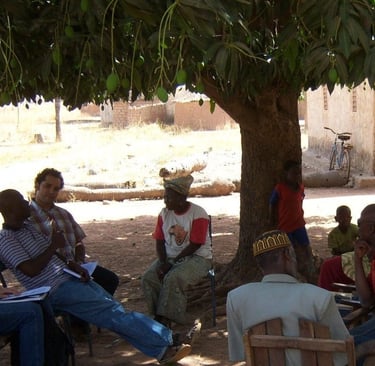

We started by finding anyone who could speak French, since our grasp of the local language was like a toddler trying to pick up a twenty-pound dumbbell. To understand the life and customs of our village hosts was an ongoing learning experience. We soon found that getting clues from those who spoke some French (mostly young men) was not the full picture. Village elders (pictured above) were more likely to give us the wisdom needed to survive and thrive in our new setting, but that would have to wait while our language studies continued.

Over time we got to know villagers from all ages and walks of life. Actually, there were only two walks of life in our host village: farming and fishing. Many did both. Farming was mostly rice fields and peanut fields. Fishing was done by floating hundreds of feet of gill nets across the river while the herring were running. Knowing the language opened up our eyes to not only what they were doing, but the “hows” and “whys” as well.

Along the way we learned certain standardized phrases that carry great meaning. After the standard greetings, like “Did you sleep well? How is your health? And your wife? And your children?” you could then get into the real reason for your neighbor’s visit.

“I’ve come to your place….” This standard phrase means that he (or she) has come to ask for something. It might be to borrow a tool. To ask for a loan. To pluck some vegetable that is obviously ready to harvest in your backyard garden. To get a ride to market next time you drive out of the village. Or any number of other things.

After this phrase, if you are in the know, you are supposed to respond, “I’ve heard.” Of course you heard, but the real meaning of your response is, “What do you want?” or “Get to the point.” Or “Okay, I know you want something, what is it?”

These types of verbal interchanges are the “polite” way of interacting. You don’t just barge in and say you need something. You ask about the night’s sleep, the family’s health, and other things first. Then you get on to “I’ve come to your place…” with the polite pause to see if you are being understood, and given the permission to continue with your request. The answer, “I’ve heard” is opening the door for the visitor to continue with what he really came for. Get it? (It sometimes takes years for us dense foreigners to catch on to things like this!)

One thing we did not realize was that these types of exchanges were supposed to be reciprocal. The give and take of village life. I have papaya trees in my yard, you have grapefruit trees in your yard, another neighbor has banana trees. When any particular fruit is in season, you harvest them as they ripen, and either eat them or try to sell them. But it is also common for a neighbor to come by and ask for one. This is fine, because it is expected that you will go by his place to ask for some fruit from his yard when it is ripe. Or a woman asks my wife to borrow her rake, expecting that someday my wife will reciprocate and ask to borrow her winnowing basket. Get the picture of this give and take culture? Well, we didn’t.

Months and months pass and we never go back to a neighbor’s hut with the phrase, “I’ve come to your place…” Why? Are we too self-sufficient? Too proud? Not interested in really being a part of village life? Or just don’t know the norms of the give and take of village living? (Guilty!)

A missionary told me his wake-up story in this area. His neighbor kept coming with requests, but one day told him, “This is not good. I always ask you for things, but you never ask me!” It is refreshing to have honest neighbors who can tell it like it is; who want to see us foreigners fit in.

With this glimpse into proper village give and take, the missionary decided to give it a try. He knew his neighbor had something he could use, so after giving him the standard morning greetings he said, “I’ve come to your place…” The neighbor gave him a wide smile, brought out two chairs, and gladly answered, “I’ve heard you. Let’s sit.” He was obviously thrilled that he could be of assistance, after many times of being on the receiving end. To be giving, now that is a treat! We rob our village neighbors of dignity, and of the opportunity to help us, as we have helped them. We need to be learners before we can be teachers. We cannot judge their way of life using our own as a standard. As Jesus said:

“A blind man cannot guide a blind man, can he? Will they not both fall into a pit? A pupil is not above his teacher; but everyone, after he has been fully trained, will be like his teacher. Why do you look at the speck that is in your brother’s eye, but do not notice the log that is in your own eye? Or how can you say to your brother, ‘Brother, let me take out the speck that is in your eye,’ when you yourself do not see the log that is in your own eye? You hypocrite, first take the log out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to take out the speck that is in your brother’s eye.” (Luke 6:38-42.)